7 Principles of Rich Web Applications

Also available in: Japanese, Russian, Portuguese.

This is a writeup based on a presentation I gave at BrazilJS in August 2014. It builds on some of the ideas I’ve been blogging about recently related mostly to UX and performance.

I want to introduce 7 actionable principles for websites that want to make use of JavaScript to control their UI. They are the result of my experience as a web developer, but also as a long-time user of the WWW.

JavaScript has undeniably become an indispensable tool for frontend developers. Its usage is now expanding into other areas like servers and microcontrollers. It’s the language of choice for introducing computer science concepts by prestigious universities.

Yet a lot of questions on its precise role and usage on the web remain a mystery, even to many framework and library authors.

- Should JavaScript be used to replace browser functions like history, navigation and page rendering?

- Is the backend dying? Should I render HTML at all?

- Are Single Page Applications (SPAs) the future?

- Is JS supposed to augment pages for websites, but render pages in web apps?

- Should techniques like PJAX or TurboLinks be used?

- What’s the precise distinction between a website and a web application? Should there be one at all?

What follows is my attempt to answer these. My approach is to examine the usage of JavaScript exclusively from the lens of user experience (UX). In particular, I put a strong focus on the idea of minimizing the time it takes the user to get the data they are interested in. Starting with networking fundamentals all the way to predicting the future.

- Server rendered pages are not optional

- Act immediately on user input

- React to data changes

- Control the data exchange with the server

- Don’t break history, enhance it

- Push code updates

- Predict behavior

#1. Server rendered pages are not optional

The first thing I’m compelled to point out is a fairly common false dichotomy. That of “server-rendered apps vs single-page apps”. If we want to optimize for the best possible user experience and performance, giving up one or the other is never a good idea.

The reasons are fairly straightforward. The medium by which pages are transmitted, the internet, has a theoretical speed limit. This has been memorably illustrated by the famous essay/rant “It’s the latency, stupid” by Stuart Cheshire:

The distance from Stanford to Boston is 4320km.

The speed of light in vacuum is 300 x 10^6 m/s.

The speed of light in fibre is roughly 66% of the speed of light in vacuum.

The speed of light in fibre is 300 x 10^6 m/s * 0.66 = 200 x 10^6 m/s.

The one-way delay to Boston is 4320 km / 200 x 10^6 m/s = 21.6ms.

The round-trip time to Boston and back is 43.2ms.

The current ping time from Stanford to Boston over today’s Internet is about 85ms (…)

So: the hardware of the Internet can currently achieve within a factor of two of the speed of light.The cited 85ms round-trip time between Boston and Stanford will certainly improve over time, and your own experiments right now might already show it. But it’s important to note that there’s a theoretical minimum of about 50ms between the two coasts.

The bandwidth capacity of your users’ connections might improve noticeably, as it steadily has, but the latency needle won’t move much at all. This means that minimizing the number of roundtrips you make to display information on page is essential to great user experience and responsiveness.

This becomes particularly relevant to point out considering the rise of JavaScript-driven applications that usually consist of no markup other than <script> and <link> tags beside an empty <body>. This class of application has received the name of “Single Page Applications” or “SPA”. As the name implies, there’s only one page the server consistently returns, and all the rest is figured out by your client side code.

Consider the scenario where the user navigates to http://app.com/orders/ after following a link or typing in the URL. At the time your application receives and processes the request, it already has important information about what’s going to be shown on that page. It could, for example, pre-fetch the orders from the database and include them in the response. In the case of most SPAs, a blank page and a <script> tag is returned instead, and another roundtrip will be made to get the scripts contents. So that then another roundtrip can be made to get the data needed for rendering.

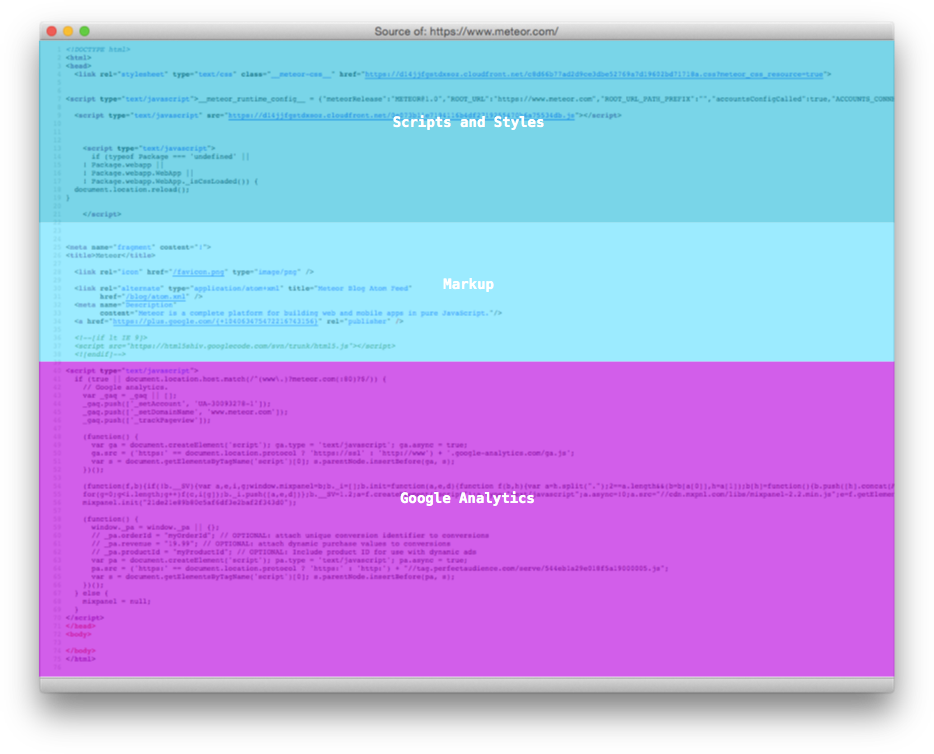

Analysis of the HTML sent by the server for every page of a SPA in the wild

At this point many developers consciously accept this tradeoff because they make sure the extra network hops happen only once for their users by sending the proper cache headers in the script and stylesheet responses. The general consensus is that it’s an acceptable tradeoff because once the bundle is loaded, you can then handle most of the user interaction (like transitions to other pages) without requesting additional pages or scripts.

However, even in the presence of a cache, there’s a performance penalty when considering script parsing and evaluation time. “Is jQuery Too Big For Mobile?” describes how even for jQuery alone this could be in the order of hundreds of milliseconds for certain mobile browsers.

What’s worse, usually no feedback whatsoever is given to the user while the scripts are loading. This results in a blank page displaying and then a sudden transition to a fully loaded page.

Most importantly, we usually forget that the current prevailing transport of internet data (TCP) starts slowly. This pretty much guarantees that most script bundles won’t be fetched in one roundtrip, making the situation described above even worse.

A TCP connection starts with an initial roundtrip for the handshake. If you’re using SSL, which happens to be important for safe script delivery, an additional two roundtrips are used (only one if the client is resuming a session). Only then can the server start sending data, but as it turns out, it does so slowly and incrementally.

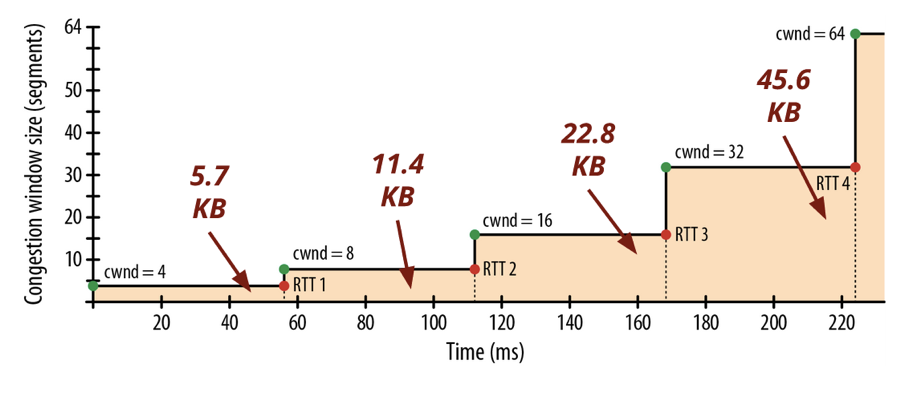

A congestion control mechanism called slow start is built into the TCP protocol to send the data in a growing number of segments. This has two serious implications for SPAs:

1. Large scripts take a lot longer to download than it seems. As explained in the book “High Performance Browser Networking” by Ilya Grigorik, it takes “four roundtrips (…) and hundreds of milliseconds of latency, to reach 64 KB of throughput between the client and server”. In this example, considering a great internet connection between London and New York, it takes 225ms before TCP is able to reach the maximum packet size.

2. Since this rule applies also for the initial page download, it makes the initial content that comes rendered with the page all that much more important. As Paul Irish concludes in his presentation “Delivering the Goods”, the first 14kb are crucially important. This is a helpful illustration of the amount of data the server can send in each round-trip over time:

How many KB a server can send for each phase of the connection by segments

Websites that deliver content (even if it’s only the basic layout without the data) within this window will seem extremely responsive. In fact, to many authors of fast server-side applications JavaScript is deemed unneeded or as something to be used sparingly. This bias is further strengthened if the app has a fast backend and data sources and its servers located near users (CDN).

The role of the server in assisting and speeding up content presentation is certainly application-specific. The solution is not always as straightforward as “render the entire page on the server”.

In some cases, parts of the page that are not essential to what the user is likely after are better left out of the initial response and fetched later by the client. Some applications, for example, opt to render the “shell” of the page to respond immediately. Then they fetch different portions of the page in parallel. This allows for great responsiveness even in a situation with slow legacy backend services. For some pages, pre-rendering the content that’s “above the fold” is also a viable option.

Making a qualitative assessment of scripts and styles based on the information the server has about the the session, the user and the URL is absolutely crucial. The scripts that deal with sorting orders will obviously be more important to /orders than the logic to deal with the settings page. Maybe less intuitively, one could also make a distinction between “structural CSS” and the “skin/theme CSS”. The former might be required by the JavaScript code, so it should block, but the latter could be loaded asynchronously.

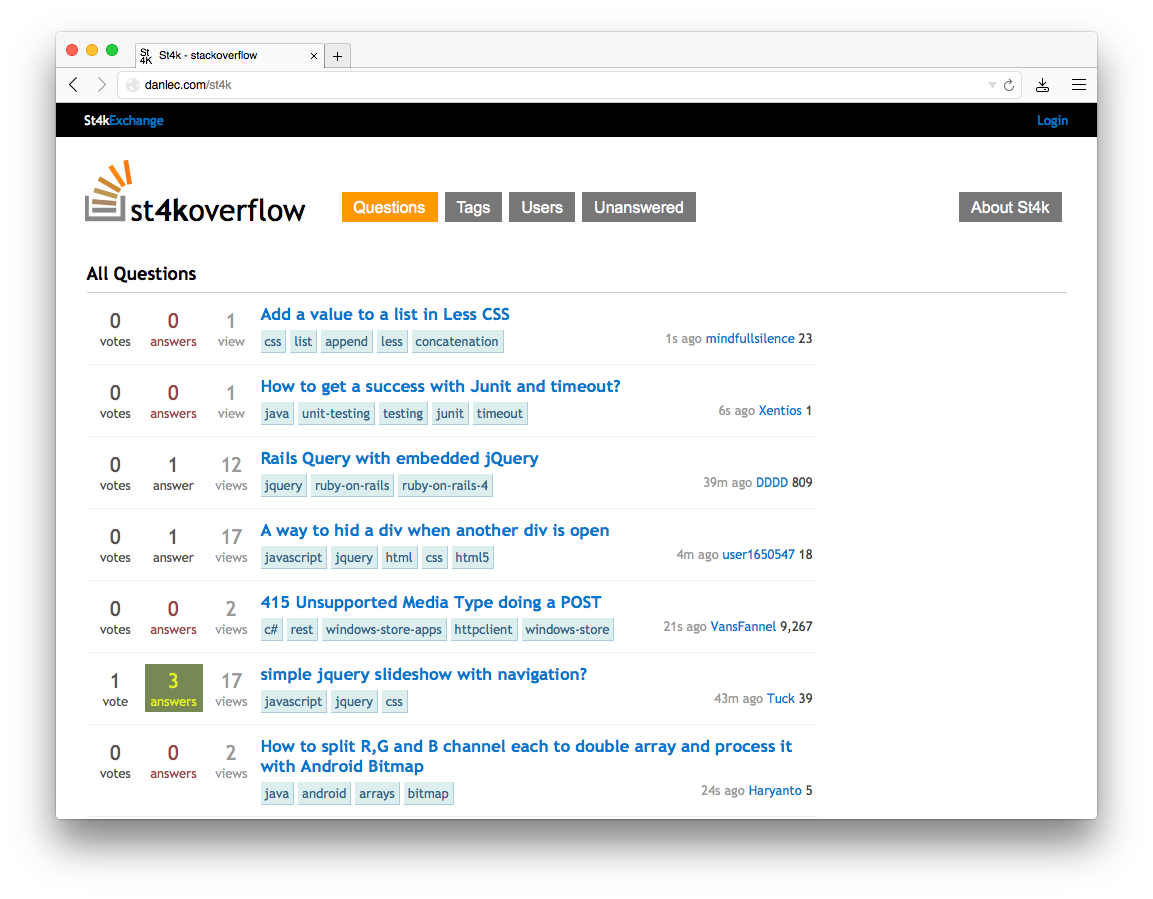

A neat example of a SPA that does not incur in extra roundtrip penalties is a proof-of-concept clone of StackOverflow in 4096 bytes (which can theoretically be delivered on the first post-handshake roundtrip of a TCP connection!). It manages to pull this off at the expense of cacheability, by inlining all the assets within the response. With SPDY or HTTP/2 server push, it should be theoretically possible to deliver client code that’s cacheable in a single hop. For the time being, rendering part or all of the page on the server is the most common solution to avoiding extra roundtrips.

Proof-of-concept SPA with inlined CSS and JS that doesn’t incur in extra roundtrips

A flexible enough system that can share rendering code between browser and server and provides tools for progressively loading scripts and styles will probably eliminate the colloquial distinction between websites and webapps. Both are reigned by the same UX principles. A blog and a CRM are fundamentally not that different. They have URLs, navigation, they show data to the user. Even a spreadsheet application, which traditionally relies a lot more on client side functionality, first needs to show the user the data he’s interested in modifying. And doing so in the least number of network roundtrips is paramount.

In my view, the major tradeoffs in performance seen in many widely deployed systems these days have to do with the progressive accumulation of complexity in the stack. Technologies like JavaScript and CSS were added over time. Their popularity increased over time as well. Only now can we appreciate the impact of the different ways they’ve been applied. Some of this is addressed by improving protocols (as shown by the ongoing enhancements seen in SPDY and QUIC), but the application layer is where most of the benefits will come from.

It’s helpful to refer to some of the initial discussions around the design of the initial WWW and HTML to understand this. In particular, this mailing list thread from 1997 proposing the addition of the <img> tag to HTML. Marc Andreessen re-iterates the importance of serving information fast:

"If a document has to be pieced together on the fly, it could get arbitrarily complex, and even if that were limited we’d certainly start experiencing major hits on performance for documents structured in this way. This essentially throws the single-hop principle of WWW out the door (well, IMG does that too but for a very specific reason and in a very limited sense) — are we sure we want to do that?”

#2. Act immediately on user input

The first principle builds heavily on the idea of minimizing latency as the user interacts with your website.

That said, despite how much effort you invest into minimizing the back-and-forth between server and client, there’s a few things beyond your control. A theoretical lower bound given by the distance between your user and your server being the unescapable one.

Poor or unpredictable network quality being the other significant one. If the network connection is not great, packet re-transmission will occur. What you would expect to result in a couple roundtrips could end up taking several.

And in this lies JavaScript’s greatest strength towards improving UX. With client-side code driving user interaction, we are now able to mask latency. We can create the perception of speed. We can artificially approach zero latency.

Let’s consider the basic HTML web again for a second. Documents connected together through hyperlinks, or <a> tags. When any of them are clicked, the browser will make a network request that’ll take unpredictably long, then get and process its response and finally transition to the new state.

JavaScript allows to act immediately and optimistically on user input. A click on a link or button can result in an immediate reaction without hitting the network. A famous example of this is Gmail (or Google Inbox), where archiving an email will happen immediately on the UI while the server request is sent and processed asynchronously.

In the case of a form, instead of waiting for some HTML as a response after its submission, we can act right after the user presses enter. Or even better, like Google Search does, we can respond to the user holding down a key:

Google adapts its layout as soon as you hold down a key

That particular behavior is an example of what I call layout adaptation. The basic idea is that the first state of a page “knows” about the layout of the next state, so it can transition to it before there’s any data to populate the page with. It’s “optimistic” because there’s still a risk that the data never comes and an error should be displayed instead, but that’s obviously rare.

Google’s homepage is particularly relevant to this essay because its evolution illustrates the first two principles we’ve discussed very clearly.

First of all, analyzing the packet dump of the TCP connection to www.google.com reveals they make sure to send their entire homepage all at once after the request comes in. The whole exchange, including closing the connection, takes 64ms for me in San Francisco. This has likely been the case ever since the beginning.

In late 2004, Google pioneered the usage of JavaScript to provide inline as-you-type suggestions (curiously, as a 20% time project, like Gmail). This even became an inspiration for coining AJAX:

Take a look at Google Suggest. Watch the way the suggested terms update as you type, almost instantly […] with no waiting for pages to reload. Google Suggest and Google Maps are two examples of a new approach to web applications that we at Adaptive Path have been calling Ajax

And in 2010 they introduced Instant Search, which puts JS front and center by skipping the page refresh altogether and transitioning to the “search results” layout as soon as you press a key as we saw above.

Another prominent example of layout adaptation is most likely in your pocket. Ever since the early days, iPhone OS would request app authors to provide a default.png image that would be rendered right away, while the actual app was loading.

iPhone OS enforced loading default.png before the application

In this case, the OS was compensating not necessarily for network latency, but CPU. This was crucial considering the constraints of the original hardware. There’s however a scenario where this technique breaks. That would be when the layout doesn’t match the stored image, as in the case of login screens. A thorough analysis of its implications was provided by Marco Arment in 2010.

Another form of input besides clicks and form submissions that’s greatly enhanced by JavaScript rendering is file input.

We can capture the user’s intent to upload through a variety of means: drag and drop, paste, file picker. Then, thanks to new HTML5 APIs we can display content as if it had been uploaded. An example of this in action is in the work we did with Cloudup uploads. Notice how the thumbnail is generated and rendered immediately:

The image gets rendered and fades in before the upload completes

In all of these cases, we’re enhancing the perception of speed. Thankfully, there’s plenty of evidence that this is a good idea. consider the example of how increasing the walk to baggage claim reduced the number of complaints at the Houston Airport, without necessarily making baggage handling faster.

The application of this idea should have very profound implications on the UI of our applications. I contend that spinners or “loading indicators” should become a rarity, especially as we transition to applications with live data, discussed in the next section.

There are situations where the illusion of immediacy could actually be detrimental to UX. Consider a payment form or a logout link. Acting optimistically on those, telling the user everything is done when it’s not, can result in a negative experience.

But even in those cases, the display of spinners or loading indicators should be deferred. They should only be rendered after the user no longer considers the response was immediate. According to the often-cited research by Nielsen:

The basic advice regarding response times has been about the same for thirty years Miller 1968; Card et al. 1991:

0.1 second is about the limit for having the user feel that the system is reacting instantaneously, meaning that no special feedback is necessary except to display the result.

1.0 second is about the limit for the user’s flow of thought to stay uninterrupted, even though the user will notice the delay. Normally, no special feedback is necessary during delays of more than 0.1 but less than 1.0 second, but the user does lose the feeling of operating directly on the data.

10 seconds is about the limit for keeping the user’s attention focused on the dialogue. For longer delays, users will want to perform other tasks while waiting for the computer to finish

Techniques like PJAX or TurboLinks unfortunately largely miss out on the opportunities described in this section. The client side code doesn’t “know” about the future representation of the page, until an entire roundtrip to the server occurs.

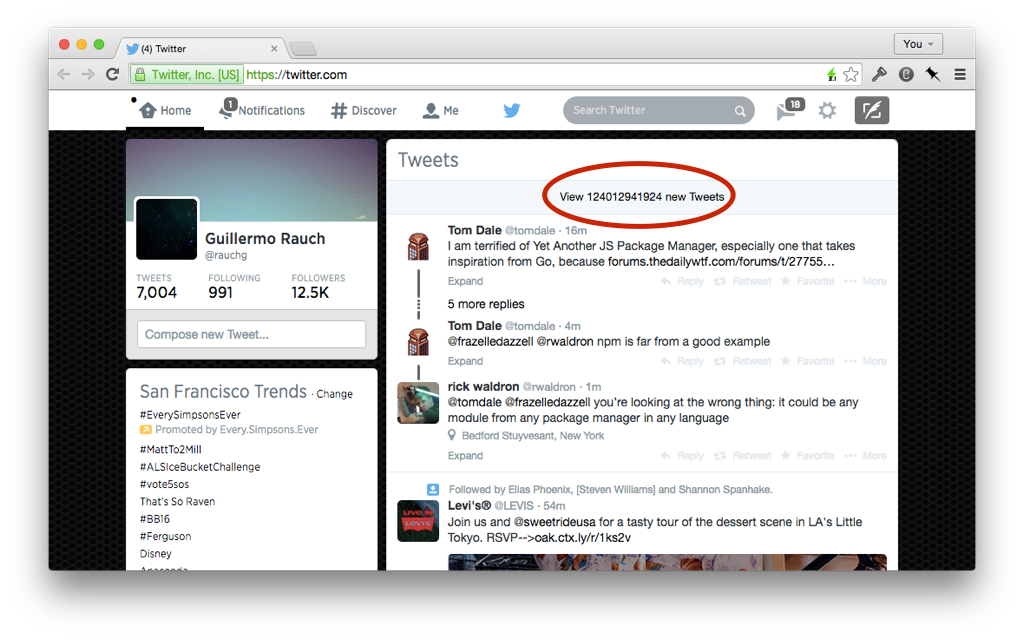

#3. React to data changes

The third principle is that of reactivity of the UI with respect to data changes in the source, typically one or more database servers.

Serving an HTML snapshot of data that remains static until the user refreshes the page (traditional websites) or interacts with it (AJAX) is increasingly becoming obsolete.

Your UI should be self-updating.

This is crucially important in a world of an ever-increasing number of data points, in the form of watches, phones, tablets and wearable devices yet to be designed.

Consider the Facebook newsfeed at the time of its inception, when data was primarily entered through personal computers. Rendering it statically was not optimal, but it made sense if people were updating their profiles maybe once a day, if that.

We now live in a world where you can upload a photo, and have your peers like it or comment on it almost immediately. The need for realtime feedback is natural due to the highly concurrent usage of the application.

It would be wrong, however, to assume that the benefits of reactivity are limited to multi-user applications. Which is why I like to talk about concurrent data points as opposed to users. Consider the common scenario of sharing a photo you have on your phone with your own laptop:

A single-user application can still benefit from reactivity

It’s useful to think of all the data exposed to the user as reactive. Session and login state synchronization is an example of applying this principle uniformly. If users of your application have multiple tabs open simultaneously, logging out of one will invalidate them all. This inevitably results in enhanced privacy and security, especially in situations where multiple people have access to the same device.

Each page reacts to the session and login state

Once you set up the expectation that the information on the screen updates automatically, it’s important to consider a new need: state reconciliation.

When receiving ordered atomic data updates, it’s easy to forget that your application should be able to update appropriately even after long periods of disconnection. Consider the scenario of closing your laptop’s lid and reopening it days later. What how does your app behave then?

Example of what would occur if we disregard elapsed time upon reconnection

The ability for your application to reconcile states disjointed in time is also relevant to our first principle. If you opt to send data with the initial page load, you must consider the time the data is on the wire until your client-side scripts load. That time is essentially equivalent to a disconnection, and the initial connection by your scripts is a session resumption.

#4. Control the data exchange with the server

When the WWW was conceived, data exchange between the client and server was limited to a few ways:

- Clicking a link would

GETa new page and render the new page - Submitting a form would

POSTorGETand render a new page - Embedding an image or object would

GETit asynchronously and render it

The simplicity of this model is attractive, and we certainly have a much higher learning curve today when it comes to understanding how data is sent and received.

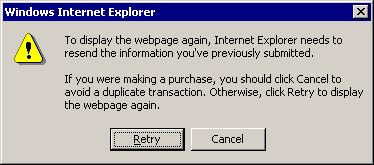

The biggest limitations were around the second point. The inability to send data without necessarily triggering a new page load was not optimal from a performance standpoint. But most importantly, it completely broke the back button:

Possibly the most annoying artifact of the old web

The web as an application platform was thus inconceivable without JavaScript. AJAX constituted a leapfrog in terms of the user experience around user submission of information.

We now have a variety of APIs (XMLHttpRequest, WebSocket, EventSource to name a few) that give us fine-grained control of the data flow. In addition to the ability to send data the user inputs into a form, we now have some new opportunities to enhance UX.

One that’s specially relevant to our previous principle is the ability to display the connection state. If we set up the expectation that the data updates automatically, we ought to notify the user about being disconnected and ongoing reconnection attempts.

When detecting a disconnection, it’s useful to store data in memory (or even better, localStorage) so that it can be sent later. This is specially important in light of the introduction of ServiceWorker, which enables JavaScript web applications to run in the background. If your application is not open, you can still attempt to sync user data in the background.

Consider timeouts and errors when sending data and retry on behalf of the user. If a connection is re-established, attempt to send the data again. In the case of a persistent failure, communicate it to the user.

Certain errors should be handled carefully. For example, an unexpected 403 could mean the user’s session has been invalidated. In such cases, you have the opportunity to prompt the user to resume it by showing a login screen.

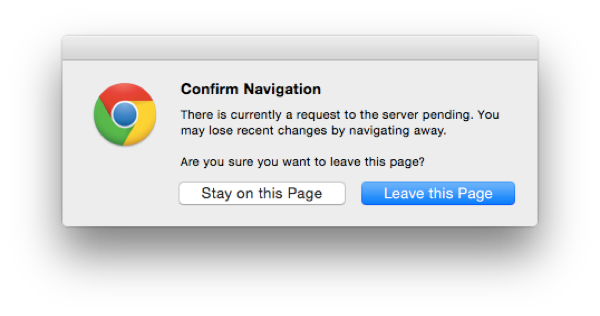

It’s also important to make sure the user doesn’t inadvertently interrupt the data flow. This can happen under two situations. The first and most obvious one is closing the browser or tab, which you can attempt to prevent with beforeunload handlers.

The beforeunload browser warning

The other (and less obvious) one is capturing page transitions before they happen, like clicking links that trigger a new page load. This gives you a chance to display your own modals.

#5. Don’t break history, enhance it

Form submissions aside, if we were to design any modern web application with only hyperlinks, we’d end up with fully functional back/forward navigation.

Consider, for example, the typical “infinite pagination scenario”. The typical way it’s implemented involves capturing the click with JavaScript, requesting some data / HTML, injecting it. Making the history.pushState or replaceState call is an optional step, unfortunately not taken by many.

And this is why I use the word “break”. With the simpler model the web proposed initially, this situation was not in the picture. Every state transition relied on a URL change.

The flip side of this is that new opportunities emerge for enhancing history now that we can control it with JavaScript.

One such opportunity is what Daniel Pipius dubbed Fast Back:

Back should be quick; users don’t expect data to have changed much.

This is akin to considering the back button an application-level button and applying principle 2: act immediately on user input. The key is that you can now decide how to cache the previous page and render it instantly. You can then apply principle 3 and then inform the user of new data changes that happened to that page.

There are still a few cases where you won’t be in control of the caching behavior. For example, if you render a page, then navigate to a third party website, and the user clicks back. Applications that render HTML on the server and then modify it on the client are at particular risk of this subtle bug:

Pressing back incorrectly loads the initial HTML from the pageload

Another way of breaking navigation is by ignoring scrolling memory. Once again, pages that don’t rely on JS and manual history management most likely won’t have an issue with this. But dynamic ones usually do. I tested the two most popular JavaScript-driven newsfeeds of the web: Twitter and Facebook. Both exhibited scrolling amnesia.

Infinite pagination is usually susceptible to scrolling amnesia

Finally, be aware of state changes that are relevant only while navigating history. Consider this example of toggling the display of comment subtrees.

The toggling of comments should be preserved when navigating history

If the page was re-rendered by following a link within the application, the expectation of the user might be that all comments appear uncollapsed. The state was volatile and only associated with the entry in the history stack.

#6. Push code updates

Making your application react to code changes is crucially important.

First of all, it reduces the surface for possible errors and increases reliability. If you make a breaking change to your backend APIs, then clients’ code must be updated. They might otherwise not be able to understand new data, or they may send data in an incompatible format.

Another equally important reason has to do with the implementation of principle #3. If your UI is self-updating, there’s little reason for users to trigger a page refresh.

Keep in mind that in a traditional website, a page refresh accomplishes two things: reload the data and reload the code. Setting up a mechanism to push data without one to push code is not enough, especially in a world where a single tab (session) might stay open for a very long time.

If a server push channel is in place, a notification can be emitted to clients when new code is available. In the absence of that, a version number can be appended as a header to outgoing HTTP requests. The server can then compare it to its latest known version, opt to handle request or not, and advice the client.

After this, some web applications opt to refresh the page on behalf of the user when deemed appropriate. For example, if the page is not visible and no form inputs are filled out.

A better approach is to perform hot code reloading. This means that there would be no need to perform a full page refresh. Instead, certain modules can be swapped on the fly and their code re-executed.

It’s certainly hard to make hot code reloading work for many existing codebases. It’s worth discussing then a type of architecture that elegantly separates behavior (code) from data (state). Such a separation would allow us to make a lot of different patches very efficient.

Consider for example a module in your application that sets up an event bus (e.g: socket.io). When events are received, the state of a certain component is populated and it renders to the DOM. Then you modify the behavior of that component, for example, so that it produces different DOM markup for existing and new state.

The ideal scenario is that we’re able to update the code on a per-module basis. It wouldn’t make sense to restart the socket connection, for example, if we can get away with just updating the modified component’s code. Our ideal architecture for hot-code pushing is thus modular.

But the next challenge is that modules should be able to be re-evaluated without introducing undesirable side effects. This is where an architecture like the one proposed by React comes particularly handy. If a component code is updated, its logic can be trivially re-executed and the DOM efficiently updates. An exploration of this concept by Dan Abramov can be found here.

In essence, the idea that you render to the DOM (or paint it) is what significantly helps with hot code swapping. If state was kept in the DOM, or event listeners where set up manually by your application, updating code would become a much more complicated task.

#7. Predict behavior

A rich JavaScript application can have mechanisms in place for predicting the eventual user input.

The most common application of this idea is to preemptively request data from the server before an action is consummated. Starting to fetch data when you hover a hyperlink so that it’s ready when it’s clicked is a straightforward example.

A slightly more advanced method is to monitor mouse movement and analyze its trajectory to detect “collisions” with actionable elements like buttons. A jQuery example:

jQuery plugin that predicts the mouse trajectory

#Conclusion

The web remains one of the most versatile mediums for the transmission of information. As we continue to add more dynamism to our pages, we must ensure that we retain some of its great historical benefits while we incorporate new ones.

Pages interconnected by hyperlinks are a great building block for any type of application. Progressive loading of code, style and markup as the user navigates through them will ensure great performance without sacrificing interactivity.

New unique opportunities have been enabled by JavaScript that, once universally adopted, will ensure the best possible user experience for the broadest and freest platform in existence.